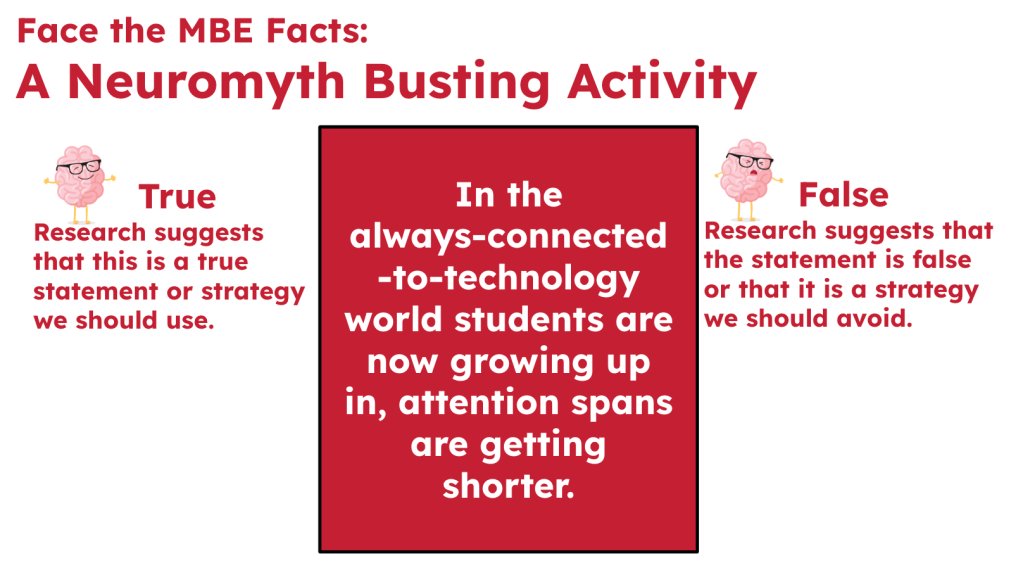

Continuing our consistent practice, we played Face the MBE Facts: A Neuromyth Busting Activity from The Center for Transformational Teaching and Learning as our warm-up. I really like these cards. They are written to provoke thought and discussion. Often, our faculty are split between true and false. The back of each card gives the True/False result and some supporting information for faculty to consider. It creates a need to know. (You should run – not walk – to get these to promote learning.) Here’s a sample:

To add some movement, I asked teachers to move to the side of the room that represents their initial thinking. After a quick standing turn-and-talk, I asked the teachers to pick someone on the other side and have another quick discussion. Let’s listen for understanding, not necessarily for agreement. (Seriously, buy these cards to play with your faculty! We were split 50-50 in our thinking, and we changed our minds after discussion. And then, we learned together.)

While we were in 100% agreement on the other two cards (Wow!), we took time to build common understanding. The next two cards stated:

Remember that reflection and meta-cognition are different.

The emotion and cognitive areas of the brain are highly interlinked, so emotional factors, like stress, anxiety, happiness, and belonging need to be considered when thinking about improving learning.

As a team, are we clear on the differences between reflection and meta-cognition? What about our ability to distinguish between stress and anxiety?

Google’s embedded AI summarized the following:

While closely related, “metacognition” refers to the act of thinking about one’s own thinking process, while “reflection” is a broader term encompassing the act of looking back on an experience to analyze and learn from it; essentially, metacognition is a specific type of reflection focused on the cognitive process itself, allowing you to monitor and adjust your thinking strategies as you go, whereas reflection can be a more general review of an experience without necessarily focusing on the mechanics of thought.

From Atlas of the Heart, Brené Brown writes

Stressed: We feel stressed when we evaluate environmental demand as beyond our ability to cope successfully. This includes elements of unpredictability, uncontrollability, and feeling overloaded. — Stressful situations cause both physiological (body) and psychological (mind and emotion) reactions. However, regardless of how strongly our body responds to stress (increases in heart rate and cortisol), our emotional reaction is more tied to our cognitive assessment of whether we can cope with the situation than to how our body is reacting.

The American Psychological Association defines anxiety as “an emotion characterized by feelings of tension, worried thoughts and physical changes like increased blood pressure.” … Worrying and anxiety go together, but worry is not an emotion; it’s the thinking part of anxiety. Worry is described as a chain of negative thoughts about bad things that might happen in the future.

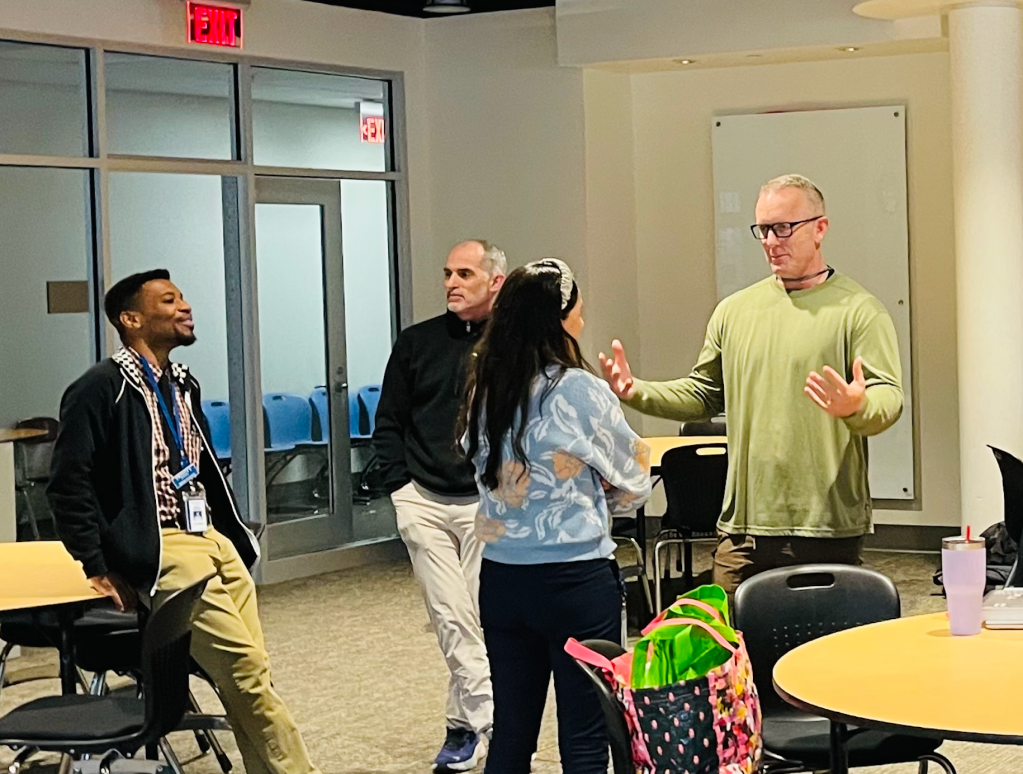

To finish this session, I asked several teachers to discuss what they’ve learned and applied and how it is going. Becky Maas, Fifth Grade Science Teacher, discussed Sousa’s Primacy-Recency and how her students now know what to expect and that a cognitive break is coming.

The primacy-recency effect describes the phenomenon whereby, during a learning episode, we tend to remember best that which comes first (prime-time-1), second best that which comes last (prime-time-2), and least that which comes just past the middle (down-time). Proper use of this effect can lead to lessons that are more likely to be remembered.

In addition, she has been working on Best Classroom Practice 1. Plan Activities That Grab Attention from Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa’s Making Classrooms Better: 50 Practical Applications of Mind, Brain, and Education Science, which tells us:

Because learners often lack the instinct to intuit the desired focus of the class’s attention, teachers must explicitly call attention to the important parts of the class. Telling students to “pay attention; this is really important” is not cheating; it is being clear.

If a student is not sure of the learning objective, she may pay attention to irrelevant aspects of the activity and therefore fail to learn.

The brain is able to focus better and pay more attention to what’s important when it knows what to look for. As noted earlier, studies in MBE show that it is impossible for the brain not to pay attention; it is always paying attention to something (Koenig, 2010).

Alyssa Gangarosa, UED Music, shared how she’s taught her students about retrieval practice to remember the Preamble to the Constitution and the words to the patriotic songs for the Veterans Day assembly. In addition, she continues to talk with our students about how to learn best. Here are my notes from my observation of one of her Second Grade classes.

Utilizing David Sousa’s Primacy-Recency timing for class, Alyssa transitioned her students to a new activity with sticks. The “game” was Becoming a Super Second Grade Lyric Learner. Alyssa had 4 slides with “which is better for your learning” slides that had this or that ideas and rhythms. Students were asked to decide which was better for learning and move to the rug’s side to “vote.” She read the statements, had all students practice the rhythm they saw, and then revealed the better answer. Students cheered when they were correct. Again, Alyssa offered immediate, corrective feedback when students were not meeting her performance expectations – kindly and with a smile.

It is really important to teach students how to learn better. What a fun way to add this in.

I hope these teachers and others will let me write about the details of their learning, work, and successes.

I ended the session by expressing gratitude for the work, engagement, effort, and learning from this cohort of faculty-learners. I am so grateful to work with teachers who learn, study, and team to improve learning.

Brown, Brené. Atlas of the Heart: Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience (p. 5-11). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Sousa, David A.. How the Brain Learns (p. 109). SAGE Publications. Kindle Edition.

Tokuhama-Espinosa, Tracey. Making Classrooms Better: 50 Practical Applications of Mind, Brain, and Education Science (p. 124). W. W. Norton & Company. Kindle Edition.