As teachers, how often do we grapple, struggle, and press our thinking in new ways? We intend and hope that our students are challenged every day? How empathetic are we when our students grapple with ideas that are challenging to them yet obvious to us?

How do we encourage our students to keep struggling when they face a challenging task? How many learners are accustomed to giving up when they can’t solve a problem instantly? How do we change the practice of how our students learn mathematics?

Effective teaching not only acknowledges the importance of both conceptual understanding and procedural fluency but also ensures that the learning of procedures is developed over time, on a strong foundation of understanding and the use of student-generated strategies in solving problems. (Leinwand, 46 pag.)

Low-floor, high-ceiling tasks allow all students to access ideas and take them to very high levels. Fortunately, [they] are also the most engaging and interesting math tasks, with value beyond the fact that they work for students of different prior achievement levels. (Boaler, 115 pag.)

Deep learning focuses on recognizing relationships among ideas. During deep learning, students engage more actively and deliberately with information in order to discover and understand the underlying mathematical structure. (Hattie, 136 pag.)

Deep practice is built on a paradox: struggling in certain targeted ways — operating at the edges of your ability, where you make mistakes — makes you smarter. (Coyle, 18 pag.)

Or to put it a slightly different way, experiences where you’re forced to slow down, make errors, and correct them —as you would if you were walking up an ice-covered hill, slipping and stumbling as you go— end up making you swift and graceful without your realizing it. (Coyle, 18 pag.)

The second reason deep practice is a strange concept is that it takes events that we normally strive to avoid —namely, mistakes— and turns them into skills. (Coyle, 20 pag.)

We need to give students the opportunity to develop their own rich and deep understanding of our number system. With that understanding, they will be able to develop and use a wide array of strategies in ways that make sense for the problem at hand. (Flynn, 8 pag.)

…help students slow down and really think about problems rather than jumping right into solving them. In making this a routine approach to solving problems, she provided students with a lot of practice and helped them develop a habit of mind for reading and solving problems. (Flynn, 8 pag.)

This term productive struggle captures both elements we’re after: we want students challenged and learning. As long as learners are engaged in productive struggle, even if they are headed toward a dead end, we need to bite our tongues and let students figure it out. Otherwise, we rob them of their well-deserved, satisfying, wonderful feelings of accomplishment when they make sense of problems and persevere. (Zager, 128-129 ppg.)

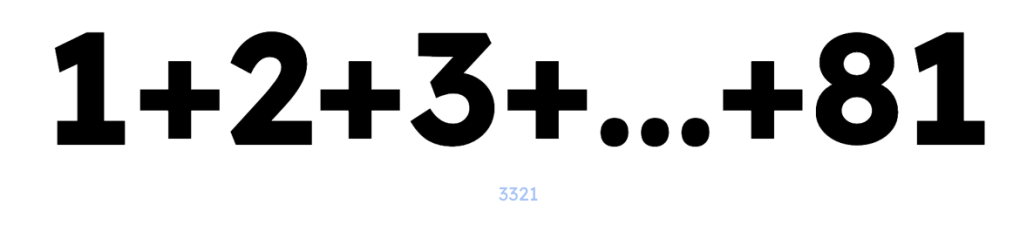

We gather to be challenged, learn more, think, and grapple. Here’s the plan:

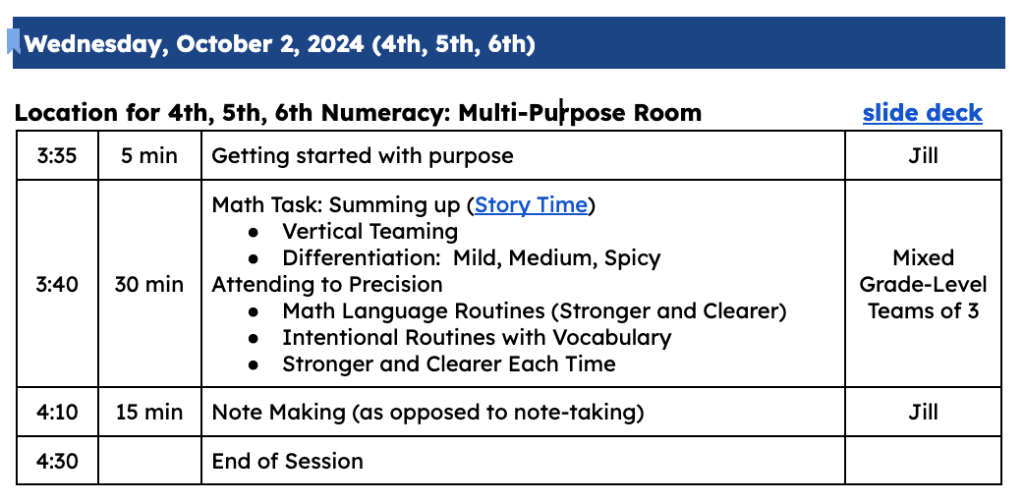

I embellished the story of Gauss and his teacher to have our teachers find the sum of consecutive natural numbers from 1 to 100. Now, mathematically this is an algebra or pre-calculus topic, but it is also adding whole numbers, making use of structure, and looking for regularity in repeated reasoning. So, there is the possibility that these teachers will find this mathematics unfamiliar.

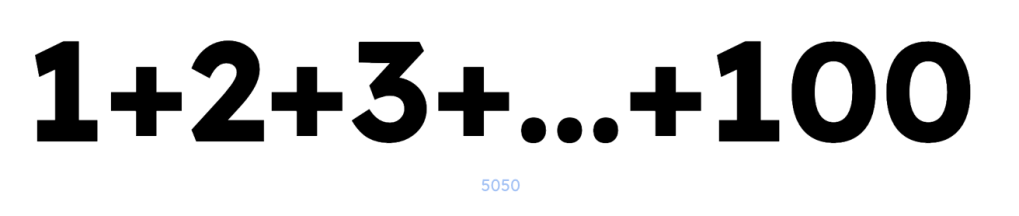

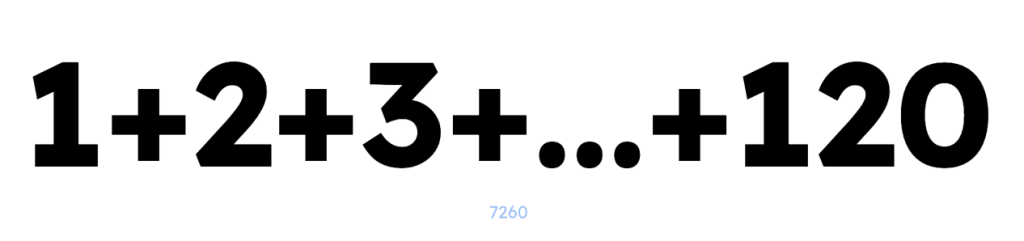

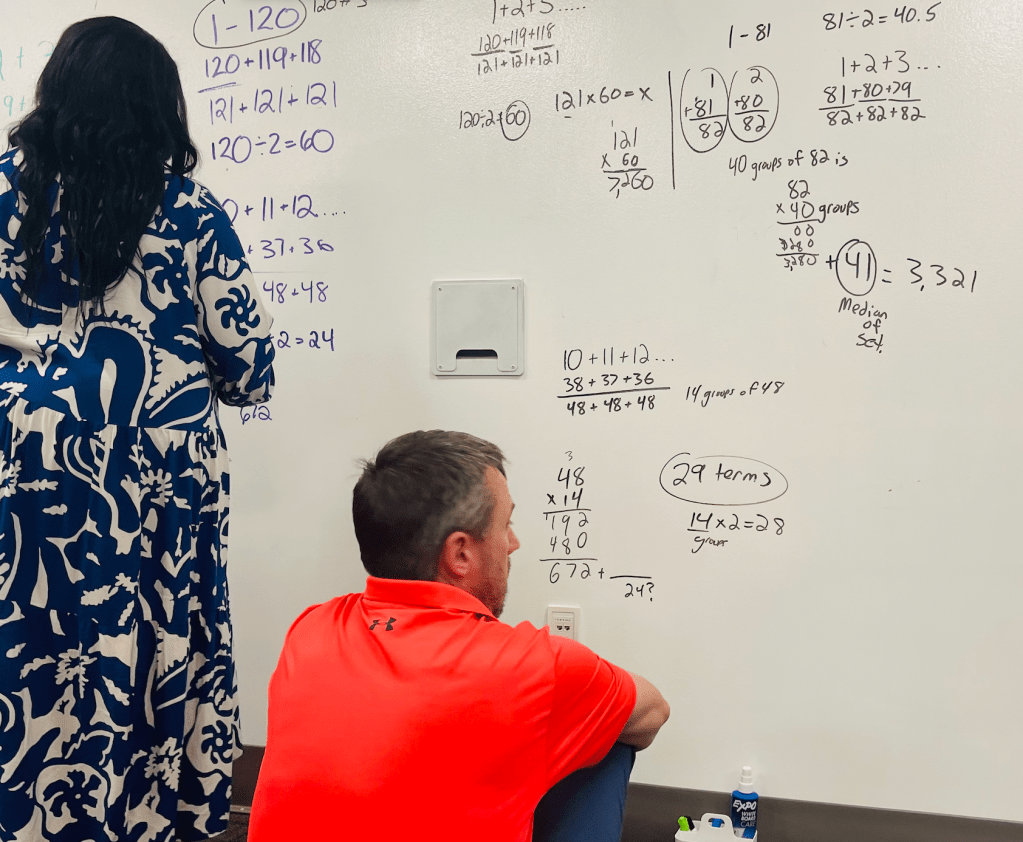

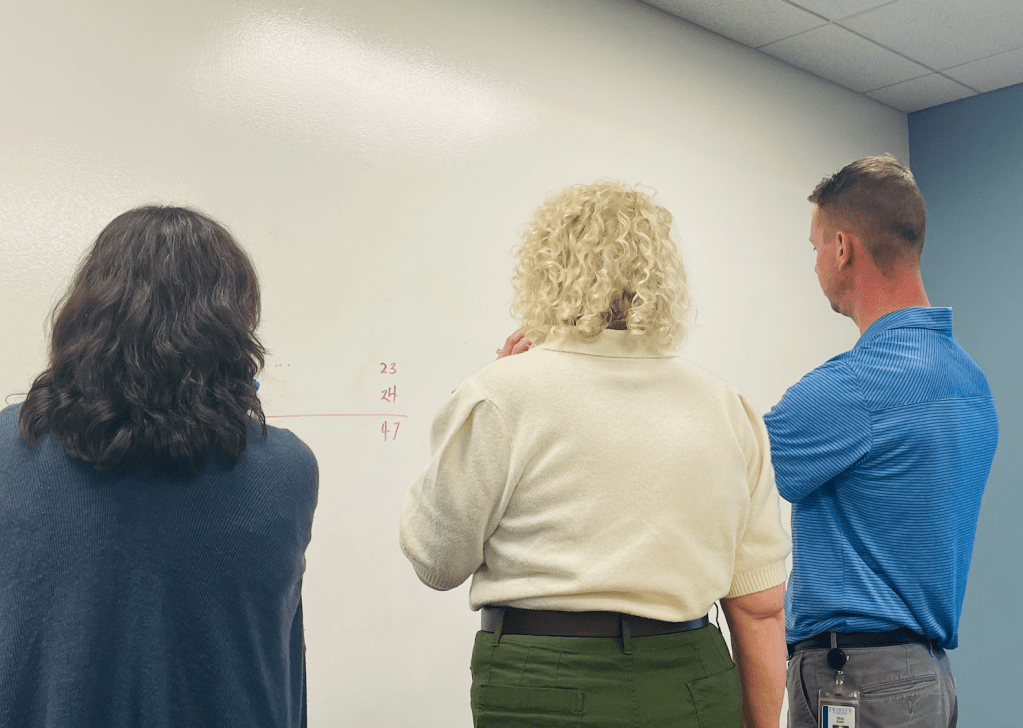

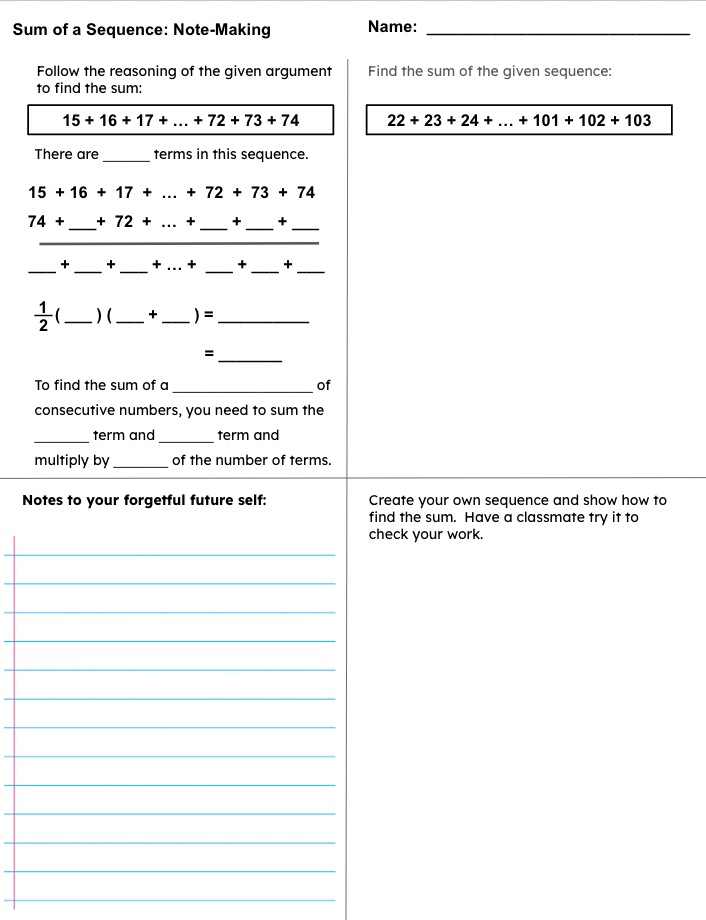

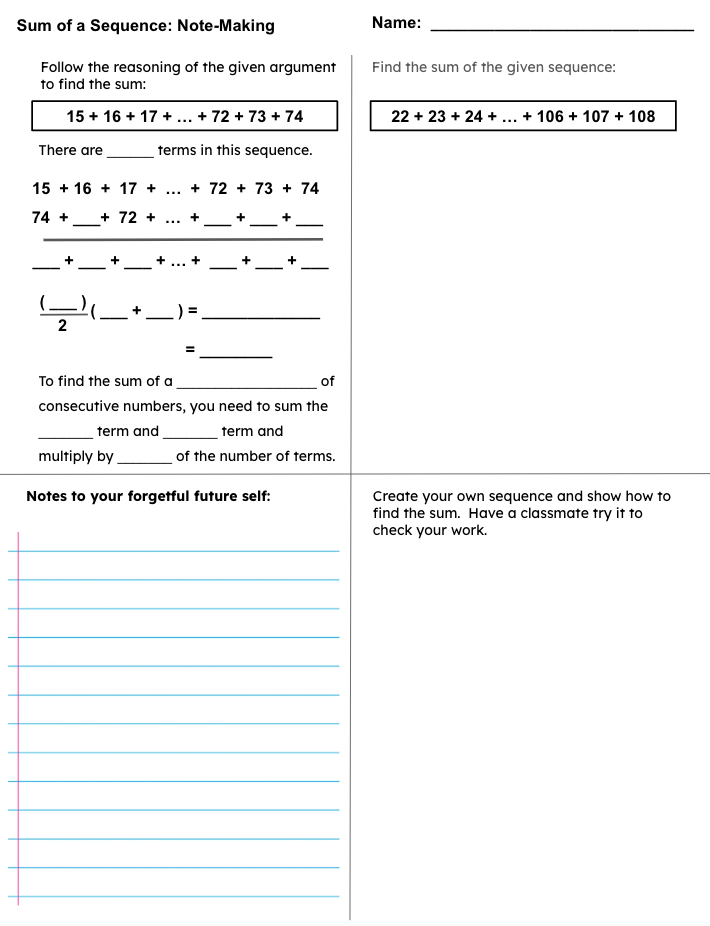

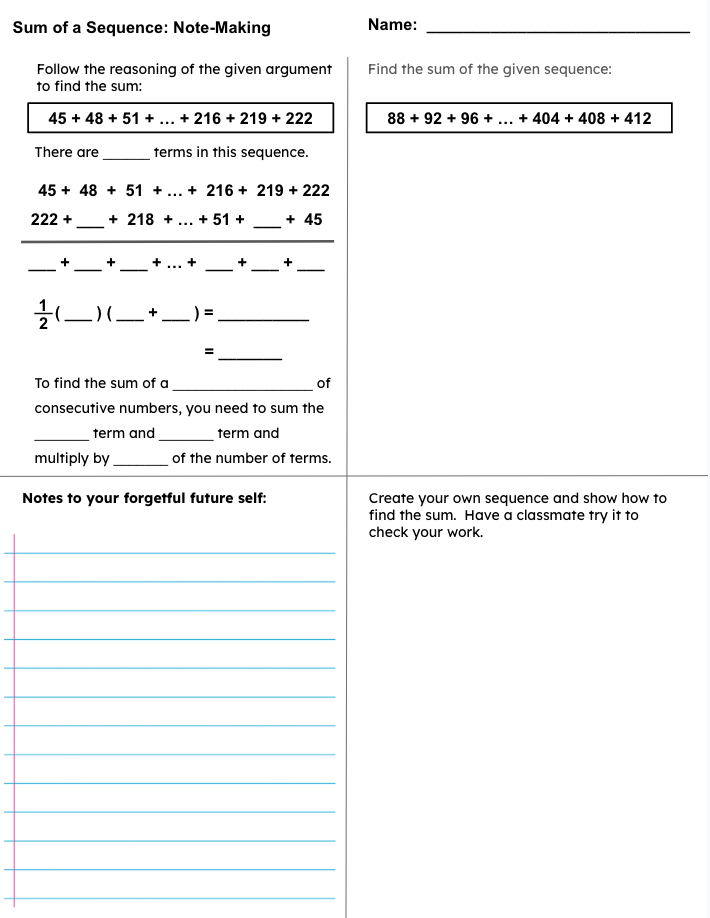

We discussed two ways to find the sum and confirmed it equals 5050. Then we worked on several more in a #BTC thin-slicing sort-of way.

When we grapple, we more readily make our thinking visible to ourselves. We try to apply this to our anticipation strategies when planning new tasks. How do we model sense-making? What needs to be made visible? What can I see or what is obvious to me that is not obvious to students? How do I model constructing an argument so that others understand my work without having to ask me questions?

We wrapped up by looking at several ideas for note-making and consolidation. We’d love to know what you think, too.

How do we encourage students to keep struggling when they face a challenging task. Change the practice of how our students learn mathematics?

Let’s not rob learners of their well-deserved, satisfying, wonderful feelings of accomplishment when they make sense of problems and persevere.

Boaler, Jo. Mathematical Mindsets: Unleashing Students’ Potential through Creative Math, Inspiring Messages and Innovative Teaching (p. 115). Wiley. Kindle Edition.

Coyle, Daniel. The Talent Code: Greatness Isn’t Born. It’s Grown. Here’s How. (p. 20). Random House, Inc.. Kindle Edition.

Flynn, Michael, and Deborah Schifter. Beyond Answers: Exploring Mathematical Practices with Young Children. Portland, ME: Stenhouse, 2017. (p. 8) Print.

Hattie, John A. (Allan); Fisher, Douglas B.; Frey, Nancy, Visible Learning for Mathematics, Grades K-12: What Works Best to Optimize Student Learning (Corwin Mathematics Series) (p. 136). SAGE Publications. Kindle Edition.

Leinwand, Steve. Principles to Actions: Ensuring Mathematical Success for All. Reston, VA.: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2014. (p. 46) Print.

Zager, Tracy. Becoming the Math Teacher You Wish You’d Had: Ideas and Strategies from Vibrant Classrooms. Portland, ME.: Stenhouse Publishers, 2017. (pp. 128-129) Print.